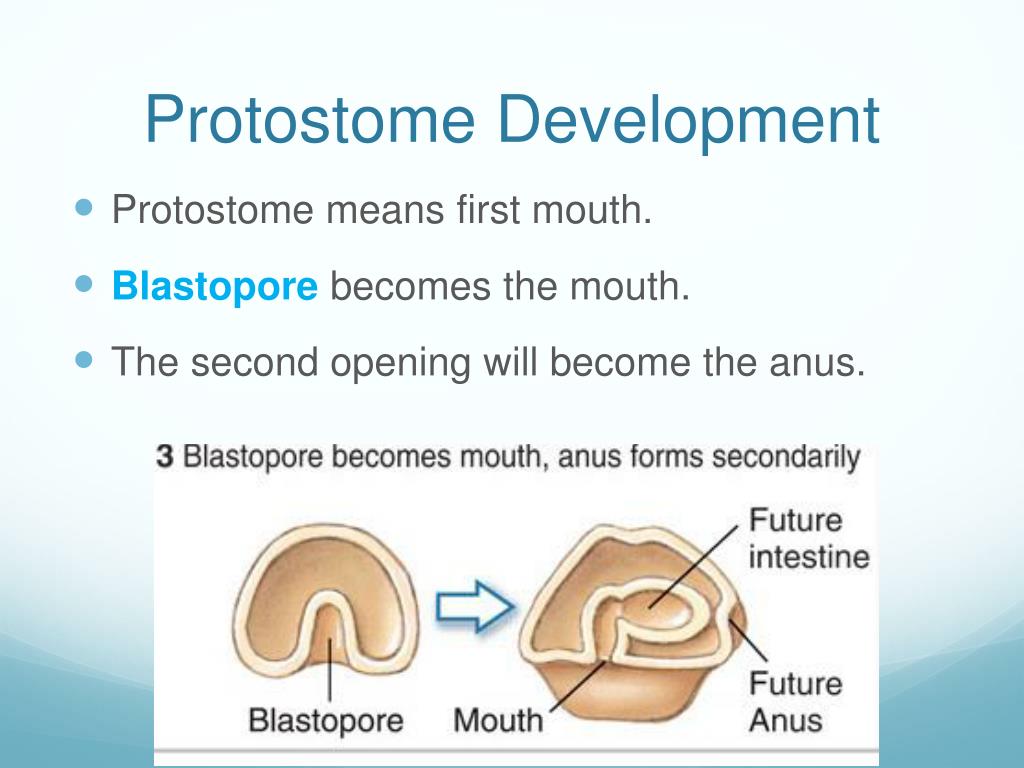

Many catch their prey by flicking out an elongated tongue with a sticky tip and drawing it back into the mouth where they hold the prey with their jaws. Nearly all amphibians are carnivorous as adults. The food may be held or chewed by teeth located in the jaws, on the roof of the mouth, on the pharynx or on the gill arches. Nearly all fish have jaws and may seize food with them but most feed by opening their jaws, expanding their pharynx and sucking in food items. Water flows in through the mouth, passes over the gills and exits via the operculum or gill slits. The buccal cavity of a fish is separated from the opercular cavity by the gills. In vertebrates, the first part of the digestive system is the buccal cavity, commonly known as the mouth. Sea urchins have a set of five sharp calcareous plates which are used as jaws and are known as Aristotle's lantern. Decapods have six pairs of mouth appendages, one pair of mandibles, two pairs of maxillae and three of maxillipeds. These include mandibles, maxillae and labium and can be modified into suitable appendages for chewing, cutting, piercing, sponging and sucking. Insects have a range of mouthparts suited to their mode of feeding. In invertebrates with hard exoskeletons, various mouthparts may be involved in feeding behaviour. Many molluscs have a radula which is used to scrape microscopic particles off surfaces. Annelids have simple tube-like guts and the possession of an anus allows them to separate the digestion of their foodstuffs from the absorption of the nutrients. Food passes first into a pharynx and digestion occurs extracellularly in the gastrovascular cavity. A fringe of tentacles thrusts food into the cavity and it can gape widely enough to accommodate large prey items. Circular muscles around the mouth are able to relax or contract in order to open or close it. In less advanced invertebrates such as the sea anemone, the mouth also acts as an anus. Anatomy Invertebrates Īpart from sponges and placozoans, almost all animals have an internal gut cavity which is lined with gastrodermal cells. More recent research, however, shows that in protostomes the edges of the slit-like blastopore close up in the middle, leaving openings at both ends that become the mouth and anus. In the protostomes, it used to be thought that the blastopore formed the mouth ( proto– meaning "first") while the anus formed later as an opening made by the other end of the gut. In deuterostomes, the blastopore becomes the anus while the gut eventually tunnels through to make another opening, which forms the mouth. In animals at least as complex as an earthworm, the embryo forms a dent on one side, the blastopore, which deepens to become the archenteron, the first phase in the formation of the gut. Indigestible waste is ejected through the mouth. Many modern invertebrates have such a system, food being ingested through the mouth, partially broken down by enzymes secreted in the gut, and the resulting particles engulfed by the other cells in the gut lining. The original gut of multicellular organisms probably consisted of a simple sac with a single opening, the mouth. A few animals which live parasitically originally had guts but have secondarily lost these structures. The vast majority of other multicellular organisms have a mouth and a gut, the lining of which is continuous with the epithelial cells on the surface of the body. This form of digestion is used nowadays by simple organisms such as Amoeba and Paramecium and also by sponges which, despite their large size, have no mouth or gut and capture their food by endocytosis. The digestive products were absorbed into the cytoplasm and diffused into other cells. The particles became enclosed in vacuoles into which enzymes were secreted and digestion took place intracellularly. In the first multicellular animals, there was probably no mouth or gut and food particles were engulfed by the cells on the exterior surface by a process known as endocytosis. Development of the mouth and anus in protostomes and deuterostomes

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)